Challenges for Culturomics Analyses

Interdisciplinarity

There are several recognized applications of culturomics to conservation that have not been well explored and many more applications that are likely to emerge in the coming years. These include recognizing conservation oriented constituencies and promoting public understanding of conservation issues. For example, exploring and shaping the evolution of conservation

culture, particularly outside of the academic environment, may be a subject worthy of further exploration with culturomics approaches. In-depth exploration of these topics in conservation would greatly benefit from expertise in areas such as cultural

evolution, digital humanities, media studies, social marketing, linguistics, and psychology. This clearly illustrates the interdisciplinary nature of many conservation culturomics projects and highlights the necessity for collaborations to enhance the reach, scope, and impact of future conservation applications.

Ethical Issues

The wealth of digital data available on the internet can be a source of potentially sensitive information, and researchers need to carefully consider the ethical implications of using such information. There are numerous examples of recorded illegal activity in digital content, including illegal wildlife trade and illegal hunting. Much digital data contain personal information, including names, locations, or photographs, that could conceivably be used to directly identify specific individuals. Indirect identifiers, including workplace, occupation, and residence, may also be available and can allow the extrapolation of direct personal information even when it has been obscured. The use of digital data for research is usually permitted in legal frameworks, especially if such data are publicly available, but the usage of personal information is more sensitive and subject to specific national or regional legislation. When personal data are collected, researchers are required to respect users´ privacy by anonymizing or pseudonymizing the data during or immediately after collection. Researchers should also consider which

data to publish, including indirect identifiers, in order to protect the personal identity of research subjects. The same rationale applies to sensitive information about threatened species, such as identity, date, and location, especially when these data are recent and not easily accessible.

Inherent Biases in the Data

Although more than half of the human population is now connected to the internet, access and participation in the digital realm can differ significantly within and between regions, including many regions of the world where conservation is a priority. Gender, age, education, and other socioeconomic, cultural, political, and geographical factors are often important drivers of data availability and representativeness. For instance, traditional and indigenous people play a critical role in biodiversity conservation, but their interactions with nature are frequently underrepresented in digital data. These biases are likely to be similar to those associated with biological recording and citizen science, which conservation researchers are more familiar with.

Existing solutions to account for biases in these research areas may be used to inform conservation culturomics research and other emerging areas of inquiry drawing from similar data sources. Furthermore, existing biases should not discourage the use of digital data but rather spur the development of methods that can generate inferences from multiple data sources. This will allow scarce research resources to be redirected toward obtaining data from less represented populations to ensure that all relevant views are considered.

Data Validation

Given the large volume of available digital data and its potential to generate quick and large-scale insights on conservation issues, it may be tempting to proceed through data gathering and analysis without considering the need for validation. However, the algorithms used to sample or generate the data for analyses are not always transparent, which can make it difficult to identify the main driver of observed patterns. Language complexity, including synonyms, homonyms, negation, and sarcasm, can also introduce additional noise and may require careful data sampling, evaluation, and filtering prior to analysis. There are also increasing volumes of digital content generated by automatized bots, which may be present in the data and influence analytical outcomes. Therefore, data and results validation are key aspects of any conservation culturomics project. Ideally, results obtained using digital data should be validated with data from independent non-digital data sources, but that is not always possible due to a lack of suitable independent data. One alternative is to use data from multiple sources to ensure that the

results returned by different corpora agree, a process that can be considered a form of triangulation with digital data. Similarly, it may be possible to obtain robust inferences from corpora composed of multiple data types (e.g., text, image, sound,

etc.) by combining their analyses. Accounting for multimodality (i.e., the presence of more than 1 data type) is an emerging topic of research in automated content analysis that is likely to be of relevance for conservation culturomics.

Data Sharing and Standards

The dynamic nature of digital data sources poses an important challenge for conservation culturomics. Changes in data access can affect ongoing projects, as highlighted above, and can also prevent the results of culturomics research from being reproduced if the original data used in the study cannot be recovered. Access to unstructured data sets generated by scraping online resources can be particularly volatile because web pages may change frequently, but even APIs and dedicated data-access platforms are updated regularly. Researchers can prevent this problem by sharing data and code in open repositories whenever possible (some data sources do not allow the redistribution of original data). One way to stimulate such efforts is to develop standards for culturomics data sharing that are applicable to multiple types of data, similar to efforts developed for biodiversity

data.

More information on challenges and biases in conservation culturomics research can be found in Correia et al. 2021, Jari´c et al. 2020a, Jari´c et al. 2020b, Di Minin et al. 2021.

There are several recognized applications of culturomics to conservation that have not been well explored and many more applications that are likely to emerge in the coming years. These include recognizing conservation oriented constituencies and promoting public understanding of conservation issues. For example, exploring and shaping the evolution of conservation

culture, particularly outside of the academic environment, may be a subject worthy of further exploration with culturomics approaches. In-depth exploration of these topics in conservation would greatly benefit from expertise in areas such as cultural

evolution, digital humanities, media studies, social marketing, linguistics, and psychology. This clearly illustrates the interdisciplinary nature of many conservation culturomics projects and highlights the necessity for collaborations to enhance the reach, scope, and impact of future conservation applications.

Ethical Issues

The wealth of digital data available on the internet can be a source of potentially sensitive information, and researchers need to carefully consider the ethical implications of using such information. There are numerous examples of recorded illegal activity in digital content, including illegal wildlife trade and illegal hunting. Much digital data contain personal information, including names, locations, or photographs, that could conceivably be used to directly identify specific individuals. Indirect identifiers, including workplace, occupation, and residence, may also be available and can allow the extrapolation of direct personal information even when it has been obscured. The use of digital data for research is usually permitted in legal frameworks, especially if such data are publicly available, but the usage of personal information is more sensitive and subject to specific national or regional legislation. When personal data are collected, researchers are required to respect users´ privacy by anonymizing or pseudonymizing the data during or immediately after collection. Researchers should also consider which

data to publish, including indirect identifiers, in order to protect the personal identity of research subjects. The same rationale applies to sensitive information about threatened species, such as identity, date, and location, especially when these data are recent and not easily accessible.

Inherent Biases in the Data

Although more than half of the human population is now connected to the internet, access and participation in the digital realm can differ significantly within and between regions, including many regions of the world where conservation is a priority. Gender, age, education, and other socioeconomic, cultural, political, and geographical factors are often important drivers of data availability and representativeness. For instance, traditional and indigenous people play a critical role in biodiversity conservation, but their interactions with nature are frequently underrepresented in digital data. These biases are likely to be similar to those associated with biological recording and citizen science, which conservation researchers are more familiar with.

Existing solutions to account for biases in these research areas may be used to inform conservation culturomics research and other emerging areas of inquiry drawing from similar data sources. Furthermore, existing biases should not discourage the use of digital data but rather spur the development of methods that can generate inferences from multiple data sources. This will allow scarce research resources to be redirected toward obtaining data from less represented populations to ensure that all relevant views are considered.

Data Validation

Given the large volume of available digital data and its potential to generate quick and large-scale insights on conservation issues, it may be tempting to proceed through data gathering and analysis without considering the need for validation. However, the algorithms used to sample or generate the data for analyses are not always transparent, which can make it difficult to identify the main driver of observed patterns. Language complexity, including synonyms, homonyms, negation, and sarcasm, can also introduce additional noise and may require careful data sampling, evaluation, and filtering prior to analysis. There are also increasing volumes of digital content generated by automatized bots, which may be present in the data and influence analytical outcomes. Therefore, data and results validation are key aspects of any conservation culturomics project. Ideally, results obtained using digital data should be validated with data from independent non-digital data sources, but that is not always possible due to a lack of suitable independent data. One alternative is to use data from multiple sources to ensure that the

results returned by different corpora agree, a process that can be considered a form of triangulation with digital data. Similarly, it may be possible to obtain robust inferences from corpora composed of multiple data types (e.g., text, image, sound,

etc.) by combining their analyses. Accounting for multimodality (i.e., the presence of more than 1 data type) is an emerging topic of research in automated content analysis that is likely to be of relevance for conservation culturomics.

Data Sharing and Standards

The dynamic nature of digital data sources poses an important challenge for conservation culturomics. Changes in data access can affect ongoing projects, as highlighted above, and can also prevent the results of culturomics research from being reproduced if the original data used in the study cannot be recovered. Access to unstructured data sets generated by scraping online resources can be particularly volatile because web pages may change frequently, but even APIs and dedicated data-access platforms are updated regularly. Researchers can prevent this problem by sharing data and code in open repositories whenever possible (some data sources do not allow the redistribution of original data). One way to stimulate such efforts is to develop standards for culturomics data sharing that are applicable to multiple types of data, similar to efforts developed for biodiversity

data.

More information on challenges and biases in conservation culturomics research can be found in Correia et al. 2021, Jari´c et al. 2020a, Jari´c et al. 2020b, Di Minin et al. 2021.

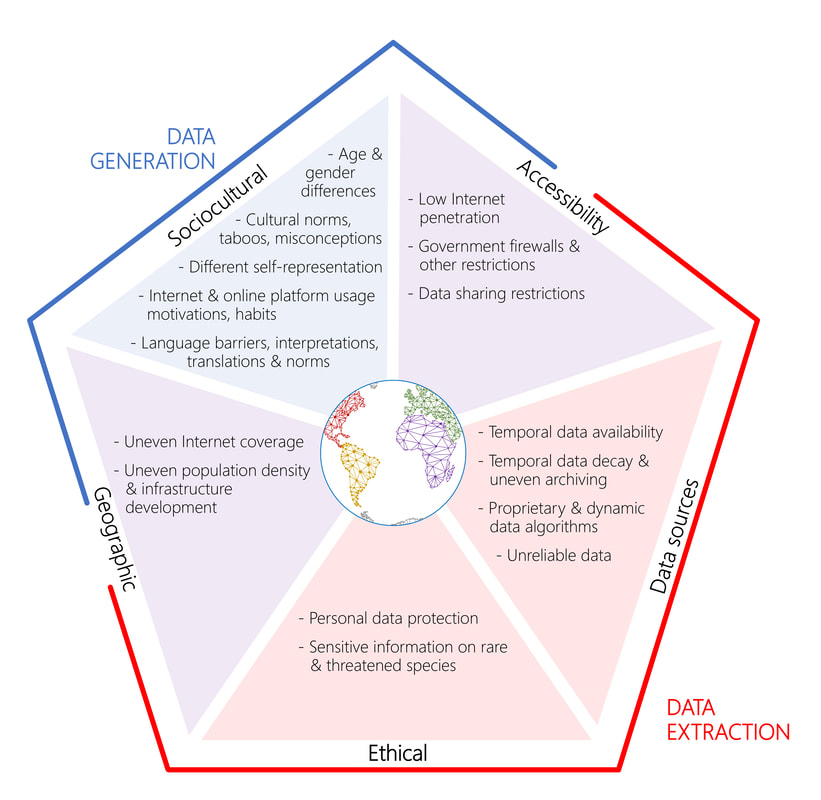

Overview of challenges and biases associated with conservation culturomics research, divided into five groups: sociocultural aspects, accessibility issues, geographic factors, issues related to data sources, and ethical issues (taken from Jari´c et al. 2020).